| From the archives of The Memory Hole |

Individualist Anarchism: Laurence Labadie

The following is James J. Martin's own introduction to a pamphlet from the Libertarian Broadsides Series, titled Laurance Labadie: Selected Essays.

Introduction

WE NEVER CALLED HIM "LARRY": A REMINISCENCE OF LAURANCE LABADIE, WITH SOME NECESSARY ADDITIONAL COMMENTS ABOUT OUR MUTUAL FRIEND, AGNES INGLIS

The death of Laurance Labadie on August 12, 1975, in his 78th year, removed from the scene the last direct link to Benjamin R. Tucker, and amounted to the virtual closure and the last episode in the socio-economic impulse which became known in the early decades of the 20th century as "Mutualism." This blending of the ideas of Josiah Warren, P. J. Proudhon, William B. Greene, and Tucker, along with peripheral contributions from Stephen Pearl Andrews, Ezra Heywood, and additional embellishments of others  less well known, was succinctly elucidated in the 1927 Vanguard editions What Is Mutualism? and Proudhon's Solution of the Social Problem, by Clarence Lee Swartz and Henry Cohen, respectively. From the early 1930s Laurance Labadie was the most polished exponent of this ideological tradition, his articulateness being commended by Tucker himself, in a dedication to a photograph he presented to Laurance dated September 6, 1936.

less well known, was succinctly elucidated in the 1927 Vanguard editions What Is Mutualism? and Proudhon's Solution of the Social Problem, by Clarence Lee Swartz and Henry Cohen, respectively. From the early 1930s Laurance Labadie was the most polished exponent of this ideological tradition, his articulateness being commended by Tucker himself, in a dedication to a photograph he presented to Laurance dated September 6, 1936.

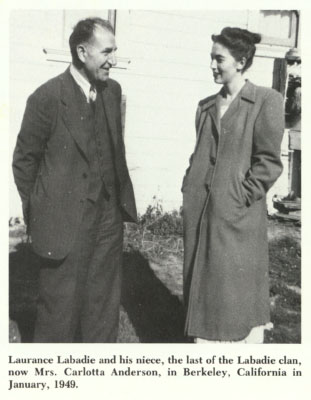

Laurance was born in Detroit on June 4, 1898. His father was Joseph A. Labadie, a celebrated figure in Detroit labor and radical activities, an almost lifelong associate of Tucker, and founder of the famed collection of printed and manuscript materials which has been housed in the Library of the University of Michigan under his name for over two generations. The family descended from mixed French and Indian stock which had settled in the Great Lakes region since the 17th century penetration of the area by the famed trappeurs and coureurs de bois. The Indian blood in the family undoubtedly had become extremely attenuated by Laurance's time, but it was part of his ancestry which he continually referred to with pride, and undoubtedly romanticized, while doing so. However, I remember spending time on several occasions examining thick albums of ancient photographs of the family, noting the reappearance generation after generation of short, stocky men, some with rather pronounced Indian physiognomy. In any case, Laurance was proud of both these ancestral strains, probably emphasized to him as time passed because he was the last of the line and sole survivor bearing the Labadie name. His only living relative is a married niece, daughter of one of his two sisters.

Laurance was the most unusual self-taught and intellectually self-disciplined person I have ever met. He learned to think and write over a long period of lonely years, perfecting his style and skills in solitary study. His teachers via literature were Tucker and the galaxy of writers in Tucker's journal, Liberty (1881-1908), Proudhon, Warren, and a substantial coterie of obscure and mainly unpublished controversialists with whom he corresponded on politico-economic themes for 40 years. But Tucker was his primary model, and he compared favorably to Tucker in clarity of expression several times.

Laurance as a letter-writer developed the most fiercely logical and precise style I have ever read, with an exceptional economy of words and absence of extraneous padding. But this characterized his other writing as well, a lengthy string of essays, very few of which were ever published. As he observed to me in his letter of May 28, 1948, "Clear and simple writing is the most difficult, if only for the reason that clear and simple thinking is so rare, and bluffing via nebulousness so easy." A related remark, which I heard from him several times, was, "When you get in deeper water you use bigger words."

The singular thing about Laurance was that he was not a professional writer or an academically-trained 'intellectual'; his formal education had barely taken him into high school, from which he thought he had providentially 'escaped' (even though secondary schools were formidable 65 years ago compared to what they are now). Unrelated even remotely to the pedagogical world of talk and print, he was essentially a skilled worker, one of the very first rank of tool makers in Detroit for years, with an accumulation of related skills which gained him the reputation of prime craftsmanship in anything he undertook. To appreciate the quality and excellence of his work one must take into consideration some of the difficulties under which men worked in the 1920s and early 1930s, before the electronic revolution, when men eyeballed tolerances of a ten thousandth of an inch. Among his talents were all the building trades: the rebuilding of much of the property he occupied for 25 years at Suffern, N.Y. (about which more later) demonstrated that. His shop on these premises was a model of compact, logical organization, even after he had become very careless about his personal affairs and habits. Here he preserved some examples of his tool-making prowess, which can only be described as exquisite.

In addition to all this, Laurance learned to set type and to operate a small job press, inherited from his father, and which the latter had used for several decades in printing his own small literary achievements, including a great deal of verse, issued sometimes in remarkable little editions often printed on the reverse side of wallpaper. This tradition of self-publication Laurance carried on for years, and a stream of small works issued from the basement of 2306 Buchanan Street, painstakingly set from fonts of tiny type by hand, locked up and run off on the small printing press. The first three essays in this collection were first produced in this manner. In the course of becoming acquainted with his father's libary, that part of it which had not been dispatched to Ann Arbor, Laurance not only learned writing style and his father's artistic achievements as a printer and publisher, but served as a preserver of several of the signal works of the individualist-anarchist tradition going back to the early 19th century; his editions of Tucker and John Badcock were especially praiseworthy.

But all this was what Laurance Labadie did in his spare time. He joined the labor force during the First World War, and began a substantial stint in the automotive industry with a job at the old Continental Motors out on East Jefferson Avenue in Detroit in 1918. He subsequently worked as well for Studebaker, Ford, and Chevrolet, in the latter becoming part of the team of advanced experimental mechanical specialists who worked closely with the designers, during the early 1920s. But Laurance changed jobs frequently, and tolerated little stupidity from foremen or other superiors. It was ironic that though he spent so many years working in the automotive industry, he never learned how to drive a car. (It was believed that Tucker never even rode in one.) Laurance worked in a number of shops during the Second World War, saved his money, and thereafter was never again employed in work involving his primary competence. Much of my personal contact with him occurred in the following five years, during which time I was pursuing graduate degrees or teaching at the University of Michigan.

The first time I met Laurance, he came out to Ann Arbor on a bus, and we conversed for a goodly span of time in the south cafeteria of the Michigan Union, where most of our conversations in the late 1940s took place. He liked the environment, with its semi-darkness and its massive oak tables carved with the initials of generations of students, and radiating a rather formidable atmosphere of respect for tradition. Here one rarely was heard to raise his voice, and there were days when there was more genuine intellectual traffic at its tables than the University's combined classrooms. Laurance loved coffee, and occasionally talked about another coffee-lover, John Basil Barnhill, editor of a famous journal of the Tucker era, The Eagle and the Serpent. (Henry Meulen, the editor in London of The Individualist, probably the only organ in the world advocating monetary ideas close to those of the Proudhon-Tucker-Labadie sort, once told a story of losing touch with Barnhill after years of contact, and then getting a cryptic postcard from him, from a Detroit hospital, which simply said, "Dear Meulen: coffee is the devil. Yours Barnhill.")

Laurance had been alerted about me by Agnes Inglis, the curator of the collection of materials housed in the general library on campus which bore the name of Laurance's father. My sustained burrowing and endless questions apparently indicated that I was serious about it all, though Laurance was somewhat wary on our first contact, long acquainted with dilettantes whose principal characteristic was the ability to ruin a good topic or subject. It did not take long to convince him I was not fooling and thenceforth we met regularly, in "the Collection," as we called it, in the Union, and on occasion at his home in Detroit on Buchanan Street. His home was easy to reach by bus from Ann Arbor. One rode it to the Detroit terminal on Grand River Avenue, then took the Grand River local out to Buchanan, got off and walked three blocks south to 18th Street; #2306 was on the corner.

Laurance's personal library was formidable, duplicating many things in the depository in Ann Arbor, but made more remarkable by his impressive correspondence files. Even at meals we 'worked,' I doing the cooking while Laurance read to me from copies of his letters to such as Henry Cohen, Gold O'Bay or E. C. Riegel and many others who became embroiled in the seemingly interminable matching especially of monetary ideas. It was this correspondence which first made me appreciate his fierce pursuit of logic and improved expression, which resulted in more clear thinking and straight writing than I have encountered from anyone else but Tucker over the years.

But we inevitably graviated to "the Collection," as most people who knew of it usually referred to it. The mark of Laurance's father "Jo" was all over it, but it had grown enormously in the more than four decades since its creation, mainly as a consequence of the tireless labors and around-the-clock devotion to Agnes Inglis, its curator until her death in 1952.

Laurance and Agnes were the first and virtually the only enthusiastic supporters I found for the writing project which eventually appeared as Men Against the State, in the five years between the completion of its first draft and its first publication. Laurance read it all for the first time in the late spring of 1949, and wrote me on June 26 of that year. "I doubt whether anyone will ever do a better job on the subject you've tackled."

Agnes was so obviously a partisan of the manuscript that it made me self-conscious, but it was a vast boost to have such unqualified support from people who knew so much about the subject as these two, and who personally knew and had known several of those figuring in the study. It provided at times a kind of eerie feeling of having been involved personally from the start as well, a feeling which was much expanded after a research residence of several weeks in New Harmony, Indiana, and another later on a Brentwood, Long Island.

Laurance had seen parts of the first three chapters dealing with Josiah Warren in 1947, and we spent some time in correspondence and conversation about Warren's ideas and activities. He remarked that after I had reported on my findings at New Harmony that he had learned more about Warren from me than I had learned from him, but I was inclined to believe that it all about evened out. And contributing to our discussions when they occurred in "the Collection" was Agnes, who responded with the radiant energy of a teenager to our ongoing reconstruction of this long-neglected story.

I guess Laurance and I both loved "Aggie," as we sometimes called her, but in our own company only. (When people started calling Laurance "Larry" I do not know, but it was after he had left Michigan. Agnes never referred to him at any time in any way except "Laurance," and everyone I ever met who knew him in the 1940s in Michigan did the same. Though his father had been known by nearly all by the affectionalte "Jo," addressing his son as "Larry" always struck me as simlar to calling Tucker "Benny.") but as to Agnes, both of us in our own personal, introverted, repressed and unexpressed ways, showed our affection through deeds instead of words. I guess there was nothing either of us would not have done for her, but she was not an easy person to do things for. It took her nearly eight years to call me by the familiar name used by all my associates, and no matter how informal things got, there was always a part of her kept in reserve. Laurance had known her for many years before I made her acquaintance, in 1943.

We occasionally went to lunch together in the Michigan League, and if the steps of the main library were icy, she would allow us to take her arm, but only until we had passed the treacherous spots; to do otherwise would have been an indication that she was no longer independent and capable of taking care of herself, even when approaching 80. That was important to her. I can remember a considerable succession of Sunday night vegetarian collations in her apartment near the U-M campus, listening to her recall ancient and exciting days, and her personal recollections of Emma Goldman, Hippolyte Havel, John Beverly Robinson and many others, among a formidable 'mist procession' of related notables; active in radical circles since World War I, she knew more people in that world than most others even read about. (The meal was almost always the same: a spread of cold cooked vegetables, especially lots of carrots, hard-boiled eggs, and a dessert of dark wheat bread toast and cherry jam, and tea. I used to spoof her mildly about her vegetarian convictions against killing animals to eat, and she acknowledged that she did break ranks by wearing leather shoes. Had she lived into the plastic revolution she might have been able to eschew even leather footwear and enjoy the last laugh on me. But she was adamant in her refusal to bless any political system for the same reason she enjoined killing animals for food: she was against any and all political solutions achieved by murder, even if such a goal was to be achieved by just one murder.)

In a letter she wrote on the evening of October 28, 1951 (a Sunday, and probably the result of thinking about our Sunday night ritual meals of the past), she remarked, "I'm 81-nearly-and frail and don't work as I have worked, but it makes everything all right. My life is full." By that time Laurance had relocated at Suffern and I was in northern Illinois. We never had another gathering in Ann Arbor; Agnes Inglis died there January 29, 1952.

Perhaps the most painful piece of writing I ever had to put together was obituarial recollection I wrote about her for David T. Wieck's occasional journal Resistance. In a routine physical examination a short time before, she was discovered to have a mild diabetic condition, and probably was worried to death by the news. She wrote me repeatedly how demeaning she felt it to be to have to visit the huge University hospital, and leaving with the feeling that she had been dealt with like a piece of furniture. My memoir was not published until the August, 1953 issue of the journal, and Laurance did not comment on it until in a letter of October 20 of that year. With characteristic feigned detachment he wrote, "I read your article on Agnes. Wieck liked it. I wrote him that you were the only person I know of who was able to write anything about her." As this introduction was taking shape, it was realized that this entire project needed this tribute to her from me, to round it out properly, and it is reprinted here as an appendix, for the first time in a quarter of a century. But for some years Laurance and I continued to speak of her as though she was still around. "The Collection" was something we talked about to the very end, even during my visit with him at Suffern in November, 1973. Most of his library went there in 1976.

An intellectual relationship with Laurance Labadie was an education in itself. Conversationally or via correspondence, he would eat you alive at the faintest sign of wavering of intelligence. The injunction against tolerating fools was something he took very seriously. One of the surest cures for an attack of the stupids, many found out, was a tangle with Laurance. As a writer, his unpretentious, stripped-down, to-the-point style (which Tucker probably would have been delighted to print in Liberty decades before), was not maimed by academic bafflegab and the waffling resulting from the fence-straddling paralysis induced by the bogus "objectivity" disease of 'hire' education, contracted from training in the sophisticated concealment of opinions behind the technical disguise of simulated aloofness or disengagement.

Laurance had always developed his economic and politico-social ideas uncluttered with theological constructs such as "natural rights," "natural law," "objective morality," and the like, a large part of these and related ideas stemming from a power position occupied by their exponents, and utterly unamenable to any kind of proof, as is the case with all religious assertions, a circumstance which accounts for the interminable arguing which all such positions encourage, and for the never-ending contumaciousness which always attends the contentions that result. (If a case for a rational and equitable libertarian order cannot be structured without recourse to religious props, then the field might just as well be abandoned to the irrationalists and it be admitted that a world ungoverned by spooks is an utter impossibility. The polemics of economics are drenched in theological postures; the earnest exposures of one another's "errors" is done in language reminiscent of religious broadsides of the early 17th century, and fanciful theses concerning likely economic behavior in the future or in defense of systems which have never seen the light of day nor are likely ever to do so are advocated with a heat comparable to that which attended the controversies of early Christianity over the nature of Transsubstantiation.)

Of all the areas of economic theory, Laurance preferred to expand upon money. After Warren, and especially Proudhon and Tucker, he respected only two modern money theorists, Hugo Bilgram and E. C. Riegel. Bilgram's The Cause of Business Depressions (New York: 1913, reprinted, Bombay, India, 1950) and Riegel's Free Enterprise Money (New York, 1944) were the only works he ever recommended to me to read. He knew Riegel personally and though he thought him the best after Bilgram, nevertheless he and Riegel engaged in sustained correspondence over points in the latter's book which were considered unclear.

It is interesting that one of the two principal modern seers of the "Austrian" school of economic theory, Friedrich Hayek, has now come around to a variant of the proposals of these and other private money exponents in the past, to the dismay of his followers, long enmeshed in the dogmas of the gold standard. (An excellent summary of Hayek's Denationalization of Money was made by the veteran libertarian econonmist Prof. Oscar W. Cooley, titled "Nobel Prize Winner Would Privatize Money," in Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, April 26, 1978, p.7-B.) In actuality, the entire individualist anti-statist position from Warren and Proudhon to the present is inextricably tied into the insistence on the necessity of competing money systems and the evolution of marketplace control over money, credit and interest rates. It is still too strong medicine for most 'libertarians,' who persist in dogged devotion to the gold standard, which is essentially a formula for a different brand of State-controlled money, run in collusion between sly State finance ministers and the major holders of gold, tying currency to a gold price fixed by agreement, and made invulnerable to the free trade in gold and consequent frequent periodic adjustments in the light of changing gold prices, by force. That this results in a money system not much different in total effect from existing fiat money systems is obvious; says Prof. Cooley, "Our dollar today, in fact, is more truly a freedom dollar than the gold standard dollar [of the past] was." The evolution of the modern State suggest that a neo-gold-standard dollar would produce an even worse situation than the now-fashionable State-manipulated issuance of unsecured paper.

I listened to many of Laurance's monologues on money theory, some of them even for some time on the telephone, only contributing my approach at the end, which was usually expressed in the simple declaration that "Money is something that will buy something," for which I was reproached for neglecting the function of money as a "store of value" and concentrating only on its function as a "medium of exchange." But he admitted that mine was surely the concern of the overwhelming majority of the people of the world. (A recent promotional piece distributed by a venerable investment brokerage house in Colorado states as a fact that of every 100 persons who reach the age of 65 in the USA, 95 of them are "flat broke.")

Perhaps I became too much of a 'Stirnerite' for Laurance. He never came to terms with Tucker's abandonment of economic and financial analysis for Stirner, and mainly tried to treat the situation as one in which Tucker's views and enthusiasms between 1881 and 1901 were all that one needed to go on. My similar waning interest in economic and money theory changed much of the nature of our communications as I gradually moved to the Pacific Coast for a decade as Laurance settled on the Atlantic. There were times when the distance separating us resulted in sustained periods of silence from both ends. In 1951 and again in 1956 I spent from late spring to early fall in nine European countries. During the first of these Laurance was laboring mightily to bring the Borsodi property, the old School of Living of the 1930s, in Suffern, into the kind of shape he wanted it to be in. I wrote him on my return, remarking that we were getting to be rather irregular correspondents. In his hasty undated reply he commented, "Yes, we've been paying about as much attention to each other as couple of brothers," while concluding, "Please tell me something about your jaunt around Urup." On the other hand there were occasions when something of mutual interest touched off a stream of dispatches back and forth. Though our personal meetings ended our other contacts made things seem as though we had never parted ways, and our more substantial exchanges concerned more the larger issues and the general circumstances attending what might be called "man's lot."

This had to be, because I was convinced that wrangling over theoretical economics was a wearisome futility, and that the ideas of economists were like those of evangelists: unprovable; one either believed them or one did not. My own experiences as a 'businessman' in the latter half of the '60s indicated to me that such things as prices were mainly psychological and a reflection more of the warfare of wills among buyers and sellers than they were of 'supply and demand' factors and production costs, frequently plucked out of thin air on an experimental basis, and sometimes arbitrarily raised, not lowered, when the product did not sell. The subject of money was similarly to be understood through psychological explanation rather than through the turning over of the tenets of theorists. Something with no intrinsic value at all was functioning as the monetary basis of the largest part of the world's surface, including the USA, simply because it was acceptable to the great majority through whose hands it passed, and in full knowledge that it had no 'redeemable' content or quality. I am still waiting for a credible explanation why a worthless material may serve as the medium of exchange among hundreds of millions for many scores of years, such a circumstance being basically uninfluenced by the hostile bellows of its critics. (The volume of literature and talk pouring out in denunciation of the money system is absolutely paralyzing in its enormity, yet this unbelievable industry amounts to little that is perceptible in the form of change; the multitudes go on exchanging goods and services for this money with barely a murmur, the whole tableau made a little humorous by the eagerness of the denouncers of the "worthless paper" to accept large amounts of it for things they have for sale, ranging from scarce substances like gold to newsletters informing the buyers that the money they use is "no good." This kind of analysis makes sophisticates smile, but they in turn are still trying to tell us how an economy functions like the man trying to explain how a gun operates by pointing to the smoke emerging from the end of the barrel after it has been fired.)

When it came to ruminations concerning the 'big picture,' we got on somewhat better, particularly in the decade of the '60s. A matter which we occasionally dwelled upon, but on which Laurance did not write other than peripherally and indirectly, was the zero record of any government solving unemployment and inflation simultaneously. Economic history did not reveal, so far as either of us could recall, a case where these two situations had ever been tackled at the same time and successfully solved; they were always taken on seriatim, and reversed when palliatives to relieve one of them exacerbated the other, requiring a turnaround of attention, and vice versa. In the 20th century there had been only emergency authoritarian regimes which had grappled with both problems at once, though the apparent degree of success had really resulted in only cosmetic solutions, producing repressed inflation and repressed unemployment via various degrees of massive governmental intervention; it was only war which seemed to come to the rescue.

Few people were more aware than Laurance that private enterprise and free enterpise are anything but synonyms, which Tucker had discussed in different terminology and under different circumstance in his famous discourse of the trusts in 1899. As for the more recent period, for nearly 60 years an army of professional anti-communists had posed the problem in Persian opposites of capitalist children of light and communist demons of darkness. But in the late 1960s they suddenly discovered that Big Industry, Big Finance, Big Commerce, and Big Agriculture (the latter controlled by the other three) got along famously with Big Communism, and that there were more unions and union members hostile to communism than there were among the opulent and the plutocratic. Then there began the serious investigation of global collusion among them, and the attention to the Bilderbergers and the Trilateral Commission, and related international string-pullers. Laurance's analysis cut through to the core of the affair well before any of the eloquent mouthpieces of the Right or Left intellectual establishment stumbled across the situation, and elaborated their topical version.

There was one matter to which we returned many times, one which had nothing to do with current affairs, world politics and national programs. This was the train of thought loosed in a celebrated book titled Might Is Right, or the Survival of the Fittest, first published in 1898 under a pseudonym, "Ragnar Redbeard," whom no one has ever identified with any certitude. It is surely one of the most incendiary works ever to be published anywhere, and was subsequently reprinted in England in 1910, and two more times in the USA, in 1927 and as recently as 1972. Laurance gave me several copies of this over the years inclduing a hardbound copy which contained his marginal comments growing out of our various discussions, in his tiny and precise handwriting, almost all in red ink. In the late '40s we drifted to this work and its various theses on several occasions, and repeatedly thereafter.

"I am still waiting for a credible explanation why a worthless material may serve as the medium of exchange among hundreds of millions for many scores of years, such a circumstance being basically uninfluenced by the hostile bellows of its critics." |

Though it was a rare incident of mutual concern which did not involve reference to historical materials, Laurance was not very enthusiastic about my involvement in teaching the subject. I agreed with him that much of which was memorialized about the past involved a vast contingent of rogues. And, when we were in a speculative mood on a galactic scale, I conceded that the affairs of the species through much of recordkeeping reflected too much concern for the deeds of the endless round of liars, thieves and murderers to which the world had been subjected across the millennia. In his sustained and deepening gloom concerning affairs domestic and foreign he found my willingness to take part in the world at least on a limited basis, simply for the fun of watching the whole loony show, as something akin to the efforts of a cheerful village idiot, diligently tending a radish garden on the lip of an active volcano.

The content of Laurance Labadie's literary labors changed considerably beginning in the early '50s and extending on for about a decade. He began to examine broader topics and confront far larger issues than those of micro-economics, which had absorbed his energies for so many of the early years of his intellectual development (Laurance stated to me that he was past 30 before taking any interest in the world of ideas). The principal reason for this abrupt change in the emphasis of his work was his early postwar involvement in the affairs and interest of the decentralist impulse, sparked by Ralph Borsodi and especially by his principal lieutenant, Mildred Jensen Loomis, a dynamic and articulate activist whose incredible energy in advancing its ideas and programs was easily the most important factor in the spread of interest in this mode of life in the quarter of a century after the end of World War II.

Borsodi's famous blast at the growing nightmare of urban industrialism, This Ugly Civilization (1929), occurred at a time before any of the later trendy and fashionable environmentalists and ecologists were even born. And his withdrawal and experimentation with a rational, logical and scientific subsistence homestead as an alternate way of life he documented in another book, Flight From the City (1933), another most premature work, which was to be an inspiration for many who were to take belated steps in his direction.

"In his sustained and deepening gloom concerning affairs domestic and foreign he found my willingness to take part in the world at least on a limited basis, simply for the fun of watching the whole loony show, as something akin to the efforts of a cheerful village idiot, diligently tending a radish garden on the lip of an active volcano." |

Beginning in 1946 the Borsodi-Loomis efforts began to take shape as the vanguard of a 'movement,' and their ideas, activities and achievements were broadcast in a series of periodicals, The Interpreter, Balanced Living, and later A Way Out. Mrs. Loomis recognized the historical continuity of the ideas dating back to Warren, Spooner, and Tucker which Laurance was mainly responsible for making known to her, and which her contemporaries were re-discovering, sometimes through just practical encounters in the everyday world. But this aspect gave to the homesteading movement an ideological base of a kind, which was incorporated into an already large body of other ideas derived from Borsodi and others. The result was that some issues of the School of Living periodicals were remarkable reading experiences, in those days thirty years ago when it seemed as though the welfare-warfare State had become all that Americans might ever know. (Laurance and I once journeyed down to Mrs. Loomis' 'base' in Brookville, Ohio in the late '40s for a long weekend, and I was immensely impressed by what she and her husband were doing on a deliberately chosen small acreage, utilizing all that could be done by maximization of rational, logical, scientific intelligence.)

A related but independent influence upon Laurance at about the same time as his contacts with the School of Living decentralists took place was the psychologist Theodore Schroeder. He spent considerable time with Schroeder at the latter's residence in Connecticut, and wrote me repeatedly concerning the subjects they discussed. It became obvious to me that Laurance increasingly appreciated some of Schroeder's views, and traces of them show up in essays written after 1950.

Laurance Labadie's extended relations with the School of Living is really a separate and necessarily far longer topic than can be taken up here. It is brought into this phase of the discussion here because it had a significant effect on what he was to write thereafter, and especially because many of the essays of this collection were produced in that period. That Laurance bought the original Borsodi School of Living property in Suffern and moved there to live in 1950 seemed to have some symbolic significance, though he never tried to do there what the Borsodi family had done 15 to 20 years earlier. (Borsodi later was to go to India for an extended stay spreading the message of his version of decentralized living.) But the periodicals edited by Mrs. Loomis were Laurance's major opening to an audience larger than that consisting of his private mail associates such as myself, and his communications and a few of his shorter pieces were published there. One of those whom he met through the agencies of the School of Living, Don Werkheiser, was responsible for Laurance's last published effort, which appeared in 1970.

A dark and morose strain began to dominate Laurance's writing in the middle of 1960s, and his work appeared so grim that it made even most editors of radical journals flinch and run. Strangely enough, one of his steadiest supporters was the editor of the Indian Libertarian, in Bombay, Arya Bhavan, who printed a succession of Laurance's pieces, though they necessarily had only a tiny exposure in America. The only attempts to print several of Laurance's essays at one time were made in 1966 and 1967 in A Way Out in special issues edited by Herbert C. Roseman, a young latecomer to the school of those who esteemed Laurance's mode of literary expression.

Actually, Laurance and I had discussed a possible edition of a collection of things which he thought had been ably done shortly after the Libertarian Book Club published my edition of Paul Eltzbacher's Anarchism in 1960. But his reaction to this suggestion was so bleakly negative then, and for some time thereafter, that it led me to abandon the project, and work at a different ones, among which were the first reprinting of Max Stirner's The Ego and His Own in almost 60 years, the first reprinting of Spooner's No Treason in a century, and a combined French and English edition of Etienne de La Boetie's Discours de la Servitude volontaire for the first time in 400 years.

It was in this latter series that I reprinted John Badcock's Slaves to Duty for the first time in a generation, using Laurance's famous basement-press Samizdat edition of 1938 (with minor corrections and a few annotations), and dedicating the edition to him. Shortly after that, in a letter on March 15, 1973, I once more proposed to him the issuance of a selection of his essays as a volume in this series. We talked about it by telephone and via correspondence for some weeks, and it was to bolt down the details, so to speak, that I flew out to see him at Suffern early in November of that year, the last time I saw him, though we spent some time on the telephone thereafter, following my return to Colorado (Laurance had some time back stopped answering his mail).

It is commonplace in the issuance of collections of this kind to accompany them with a send-off consisting of a learned disquisition on the galactic meaning of it all, an "in depth" probing of the author in virtually every dimension, and an attempt to tell the reader all about his thought processes and especially his secret ideological leanings, spelled out almost as if each contribution required hand-leading and spoon-feeding, lest the reader, if left entirely to his or her own resources, might emerge from the experience still wondering what was supposed to have been found. But this symposium has nothing pretentious in it to require such a puff. It is my conviction that Laurance Labadie, a self-taught workingman for most of his life, wrote directly enough to be understood by anyone with residual common sense and perhaps a dictionary, and the willingness to re-read what had not registered the first time around. Laurance remarked to me several times that he learned to write with great pain (usually while conveying a mixture of chiding and admiration aroused by what he alleged was my "effortless ability" to express myself); anyone who finds him hard going owes him an extra one if only because of his difficult journey from such a distant location. And the Boneless Wonders who long ago adopted a course based on Voltaire's observation that language is a device for the concealment of thought might profit from an auto-didact who never learned the ways of calculated obscurantism.

We live in a time of compounded hypocrisy of such scope and sophistication that not many seem able to apprehend the nature of it all, let alone possess or come by the intellectual tools necessary to penetrate even its outer layers. We hear form the loudest of our pacemakers what amounts to a constant psychological warfare, though purporting to advocate with mind-numbing decibels 'balance,' 'moderation,' 'intellectual and academic freedom,' the 'need to know,' as well as many other civic virtues such as 'the right to hear both sides' and the like (few issues have just two sides, but the convention which is draped upon us all starts with this crippling assumption).

So in the interest of all this, assuming a residual degree of belief in the genuineness of these and other related near-platitudinous verbal reflexes, this edition is presented as a contribution to the general illumination of the ideological community, as what a self-taught isolate, at great personal cost, thought of the world and some of its perennial concerns, as opposed to the mountain of polished evasion and cleverly phrased diversions, continuously added to by the multitude which ceaselessly emerges from the formal educational and idea-manufacturing sector, which bears official blessing and sanction as the proper basing point the remainder of us should use in confronting what Proudhon described as "the social problem."

Spring-summer, 1978

James J. Martin

Palmer Lake and Colorado

✳ ✳ ✳